正文

VOA慢速英语:新基因试验有助于发现食物中毒

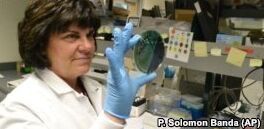

American scientists are using genetic markers to investigate food poisoning cases linked to romaine lettuce. The Associated Press reports that their use of genetic sequencing is completely changing the discovery of bacteria in food.

Genetic sequencing is being used to strengthen investigations and, in some cases, find links between what once seemed to be unrelated diseases. The technology also is uncovering once unknown causes of food poisoning.

One such example involved apples covered in caramel, a popular treat in the United States.

Up to now, scientists have been looking mainly at one bacteria: listeria. But the search is expanding. By the end of this year, laboratories in all 50 states are expected to also be using genetic sequencing for more common causes of food poisoning. That includes salmonella and the E. coli bacteria linked to the romaine lettuce outbreak.

The new technique is also helping disease scientists identify food contamination even before it causes people to get sick.

Lawyer Bill Marler has taken companies to court when their food products sicken people. He said the technique is changing how outbreaks are discovered.

Marler said the testing program is still young. He said it is too early to call genetic sequencing a success. But he said it may change how and when outbreaks are found.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, supports the program. It estimates that 48 million Americans get sick from food poisoning each year. And 3,000 of those people die from such infections.

The use of genetic sequencing involves something called whole genome sequencing, which has been used in biology for more than 20 years. A genome is a kind of genetic map. It contains all of the genetic information, or DNA, about an organism. DNA is short for the term deoxyribonucleic acid.

The laboratory process identifies most of an organism's DNA. And scientists use computer programs to compare the DNA of test specimens to see if they are the same as the organism and how resistant they are to current medicines.

The technique makes the lab studies faster, less costly and more automated, said Robert Tauxe, one of the CDC's leading experts on food poisoning.

Plans are to use the technology against several bacteria that cause food poisoning. But to date, all of the tests have involved listeria. The bacteria causes around 1,600 cases of food poisoning nationwide each year. But it is a very deadly infection, killing nearly one in five people who get it.

It can take weeks for people to develop signs of the disease. In the past, some patients died by the time health officials began to recognize the problem.

For nearly 15 years, from 1983-1997, only five listeria outbreaks were identified in the United States. They were relatively large, with an average of 54 cases for each outbreak.

That is how it was with other food poisoning outbreaks.

Tauxe said most foodborne outbreaks were found because they happened in one place, like a town with a popular eatery where people became sick.

Outbreaks were studied by asking people what they ate before they got sick. Investigators then compared notes to see what patients had in common.

But the science took a big step in the 1990s, after a major outbreak happened in the Seattle, Washington area. Four deaths and more than 700 other infections eventually were linked to undercooked hamburgers from a Jack in the Box restaurant. The meat contained the bacteria E. coli.

The outbreak led the CDC to develop a program that used a technique called pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. With this, investigators could look at a bacteria's DNA in parts. The program helped health officials more easily link cases. But it was not perfect. It was unable to make exact matches and sometimes missed when cases were related.

Then came whole genome sequencing.

The CDC began using the technique in food poisoning investigations in 2013. In the beginning, state laboratories sent samples to a CDC laboratory in Georgia for testing. Now, the CDC is working to make the technology available in all 50 states.

I'm Alice Bryant.

Mike Stobbe wrote this story for the Associated Press. Alice Bryant adapted it for Learning English. George Grow was the editor.

- 上一篇

- 下一篇

手机网站

手机网站